Adrien Brody is back with another “-ist” movie: this past year’s The Brutalist, directed by Vox Lux actor-filmmaker Brady Corbet. Financed on just $10 million, Corbet launched his 3.5-hour epic following Laszlo Toth, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor and former architect. Fleeing to the U.S. to escape persecution, he seeks freedom and success in a new land. Shot in glorious VistaVision, The Brutalist remains true to its period settings while approaching the American Dream with a grimy undercurrent, examining the juxtaposition between the hope of America and the underlying traumas of the immigrant experience. Recently nominated for ten Academy Awards, The Brutalist is positioned to be a prime contender as Adrien Brody seeks to win his second Oscar following his performance in The Pianist nearly twenty years ago. In that case, is The Brutalist a sweeping, epic destined to stand the test of time? Or, is it as hollow as its Brutalist architecture?

What’s it all about?

The film opens with Laszlo Toth (Adrien Brody) arriving at Ellis Island, facing the Statue of Liberty after escaping the Buchenwald concentration camps. Forcibly separated from his wife Erzsebet (Felicity Jones) and niece Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy), Laszlo connects with his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola) in Philadelphia. Now assimilated into American culture, Attila owns a furniture shop and is married to a beautiful gentile from Connecticut. The son of wealthy industrialist Harrison Van Buren, Harry (Joe Alwyn), commissions him and Laszlo to renovate his father’s study as a birthday surprise. The two men transform the study into a modern architectural triumph. Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), however, is none too happy and demands them to leave. Blaming Laszlo for the botched business deal along with his wife falsely accusing him of making a pass, Attila kicks him out. Destitute, Laszlo becomes a heroin addict shoveling coal for construction companies. Incidentally, the study becomes a topic of notoriety among the Philadelphia elite. So, as an admirer of art and architecture, Van Buren apologizes to Laszlo and invites him to his home where he commissions an ambitious community center in Doylestown, Pennsylvania in honor of his late mother. Now connected with important people, Laszlo brings his wife and niece to the United States. The rest of the film follows Laszlo’s journey to complete the community center, facing triumphs and setbacks along the way. As he grows increasingly disillusioned with the American Dream and the immigrant experience, he longs to create an artistic legacy that endures beyond his lifetime.

It’s a stunner!

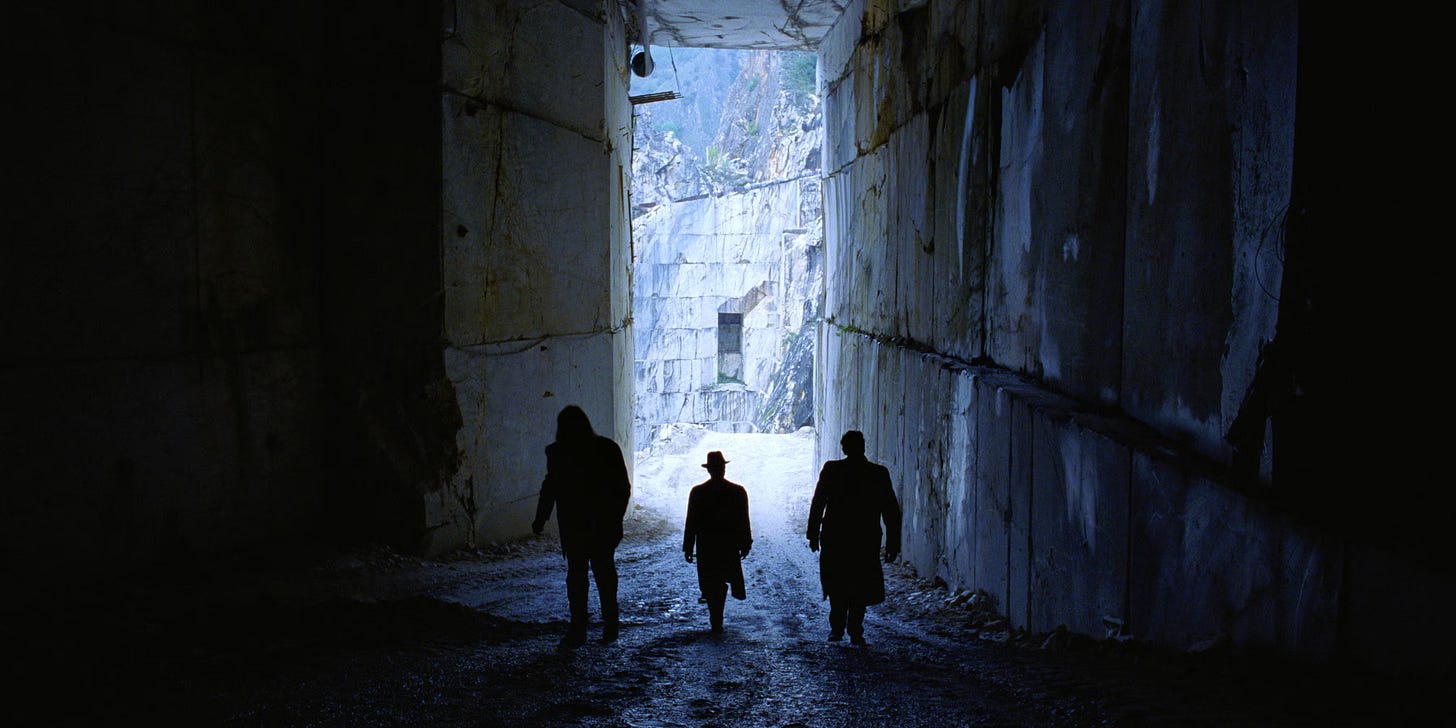

Say what you will (or what I will), but The Brutalist is hands down one of the most stunning films to look at. Nobody would believe it when you tell them it was independently financed for only ten million dollars. Similar to the buildings Toth designs, the imagery has a permanent quality. When Toth first arrives in the United States, the cinematography adopts a street photography aesthetic, with each frame meticulously composed like a work of the finest photographers. Then, as he moves up the ladder, the film’s look progresses toward painterly compositions only for the gritty photography to return once it all comes crashing down. Cinematographer Lol Crawley and director Corbet craft each shot with meticulous detail, seamlessly reflecting the mind and artistic vision of the legendary architect at the film’s center. This is bolstered by Corbet’s decision to shoot in VistaVision, a format that’s period-accurate (created in the 1950s) but also allows for greater dynamic range, reduced grain, and richer colors. The film fully utilizes the format to enhance the architectural themes, which are deeply tied to the protagonist’s past. Laszlo views his buildings as artistic expressions of his life experiences and trauma, a concept brought to life with precision by production designer Judy Becker. The period accuracy is particularly impressive, exhaustively recreating Philadelphia and New York City in the 1950s. Brady Corbet’s direction ensures that every visual element is precisely crafted, creating a masterful exercise in world-building that reflects Laszlo’s unique perspective on his surroundings. He also deftly combines classical and experimental styles to find the right cinematic language to tell the story either through inventive editing techniques or elaborately constructed long takes. The Brutalist remains an absolute triumph in bringing a singular directorial vision to life as every element of the film production shines through. One can understand comparisons to classic epics like The Godfather Part II or Once Upon a Time in America to describe the visual effect The Brutalist has. This feeling also extends to the score by Daniel Blumberg which contains echoing moments of utter beauty along with an imposing muscularity. It swerves from light jazz horns to bellowing bouts of piano, brilliantly reflecting the oscillations of Toth’s psyche to a tee. If it wasn’t for Blumberg’s powerful score, many moments would have fallen flat. The Brutalist is a stunning production from top to bottom and all kudos should go to Brady Corbet for bringing it all together.

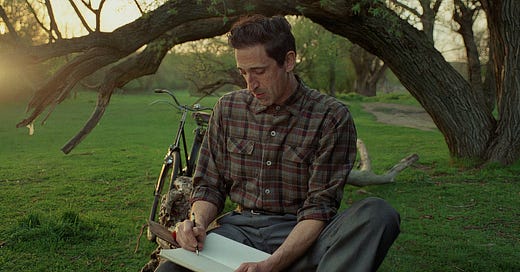

Trading Pianos for Buildings

Adrien Brody is truly transcendent, embodying Laszlo with an authenticity that goes beyond acting—he simply is the character. From the first moment on screen, his presence is undeniable, conveying deep sorrow and the weight of trauma even when the film maintains a sense of detachment. His accent work, physicality, and even his sharp comedic timing make for one of the most remarkable performances of the year. He absolutely mesmerizes to the point where individual scenes outshine entire performances I’ve witnessed this year. Brody has always been an elite performer from the very beginning, someone I put on par with Day-Lewis and DiCaprio in terms of pure talent. His tour-de-force remains his turn as Wladyslaw Szpilman in The Pianist, bringing out the guttural intensity in a tale of survival against insurmountable odds. Ironically, his turn in The Brutalist similarly explores the enduring effects of trauma, this time within the context of the American Dream, where the weight of past suffering shapes his pursuit of success in a cold, unforgiving society. Some bad career decisions here and there stripped Brody of what was supposed to be a sustained career of artistic promise. Thankfully, he’s been a mainstay of Wes Anderson’s troupe and was quite wonderful as Pat Riley in HBO’s Winning Time. That said, Brody should surely be on his way to a second Gold statuette in his turn as Laszlo. Guy Pearce is equally compelling, perfectly capturing the refined yet ruthless nature of old-money elites, shifting flawlessly between charm and cold narcissism. Meanwhile, Felicity Jones, Joe Alwyn, and Raffey Cassidy deliver strong supporting performances, with Jones especially standing out.

Far away

Unfortunately, these performances work in spite of the film. A major issue that persists is the editing, especially with regard to time jumps. I understand the film aims to capture the essence of a man—a tall task—but its frequent time jumps hinder character development. Time is often spent on events that occur between formative moments not during, leaving critical character motivations and decisions frustratingly ambiguous. At times, the performances make up for it but actors can only do so much. Most of these snags occur in the second half when more characters, plot points, and themes are thrown at us. The influx of events and information cloud many of the characters especially Laszlo and Van Buren. Even with such a long runtime, the second half feels rushed in an awfully off-putting way. Even basic screenwriting tenets are disobeyed, often setting up key character flaws or backstories to ultimately be ignored or tossed away. It seems the pressure to explore heavier themes weighed on Corbet, plummeting the film away from the gradual pace of the first half. It’s clear he can tell a great story, but in a ditch effort to make the film more “important” and to “deconstruct” the American Dream, he loses the plot (literally and figuratively). Sometimes, a compelling narrative and well-drawn characters can naturally convey deeper themes without banging our heads over with them. What we have here is not the feather but the entire chicken. There’s a moment toward the end of the film that I won’t spoil, but one that’s emblematic of Corbet’s decision to sacrifice authentic storytelling for ham-fisted symbolism that throws a wrench in the whole magnificent enterprise.

What could have been

Moreover, the film's insights on themes such as immigration, Jewish identity, and social class are not only overly spelled out but are largely clichéd. It’s quite shocking to see a filmmaker with an immense penchant for filmmaking fall short in providing meaningful commentary, so many of the arguments are laden with the same level of nuance provided by a 24/7 news cycle. There’s a lot of talk about how The Brutalist has successfully inverted the American Dream and I can’t see where. The idea that no matter how hard you work, there’ll always be someone richer, more privileged, and more gentile who’ll tear you down is not exactly new ground. To truly break new ground, the film would need to challenge or dissect these issues in a way that feels personal and deeply felt by the filmmaker. Unfortunately, Corbet’s takeaways on these issues feel a dime a dozen. The film might have been stronger had it leaned away from these well-trodden themes and instead devoted more time to Laszlo’s desire for artistic immortality—the need to be remembered. The film is perhaps at its best when it functions as an allegory for the trials and tribulations of art and the sacrifices required to leave a lasting mark. This is where Corbet’s perspective truly lies, having never experienced a percentage of the hardships Laszlo goes through (as far as we know). It all comes down to an intentional avoidance of deeper character exploration, reducing pivotal aspects of Laszlo’s journey—such as his heroin addiction—to mere details rather than something that contributes to the core of these characters. This is ironic considering Brutalist architecture revolves around stripping down buildings to their least superfluous and yet the film is chock-full of detail but devoid of soul.

Empty Ambitions

Ultimately, The Brutalist fails to live up to its ambitious potential, which is a damn shame. Adrien Brody gives another career best along with outstanding supporting help. It boasts some of the most striking imagery and attention to detail in a film this year. The abrupt ending and haphazard final act leave the audience questioning why they’ve spent 3.5 hours with these characters. In an effort to tackle too much, The Brutalist slowly loses its identity, straying away from what made the first half so compelling: the characters. It’s hard to fault a film that works so hard to achieve something of permanence but Corbet gets in his own way. Frankly, I don’t think I’ve had so much negative to say about a film that floored me on several occasions. I certainly didn’t want to feel this way as I was looking forward to Corbet’s epic. Thankfully, he is young and has a long career ahead of him. And, with only 10 million dollars, he’s crafted a film that looks ten times more expensive, which in this day and age is a feat unto itself. Yet, the bottom line is The Brutalist is like a finely assembled, innovative dish at a 5-star restaurant that initially impresses, but as you continue, you realize the chef forgot to add salt.