The master of whimsy has returned. Perfecting a style often parodied, Wes Anderson premiered The Phoenician Scheme at this year’s Cannes Film Festival to mildly positive reviews. Anderson is the quintessential “either you like him or you don’t” filmmaker. His latest was announced shortly after the release of Asteroid City two years ago. Upon reading the synopsis, I was excited to see Wes return to a grounded story with fewer characters than the ensemble-laden misfire that was Asteroid City. Announced as a father-daughter story set in an espionage genre, I was excited for Anderson to return to the humanistic cinema that made him famous in the early aughts instead of the large mosaics of perfection he’s grown obsessed with. But my expectations dropped once news came around that Tom Hanks, Scarlett Johansson, Bryan Cranston, Benedict Cumberbatch, and the usual suspects from Anderson’s stock company were attached. It brings us to the question everybody’s been asking. Has Wes Anderson lost his way? Or is The Phoenician Scheme a logical evolution of the filmmaker’s patented style?

What’s it all about?

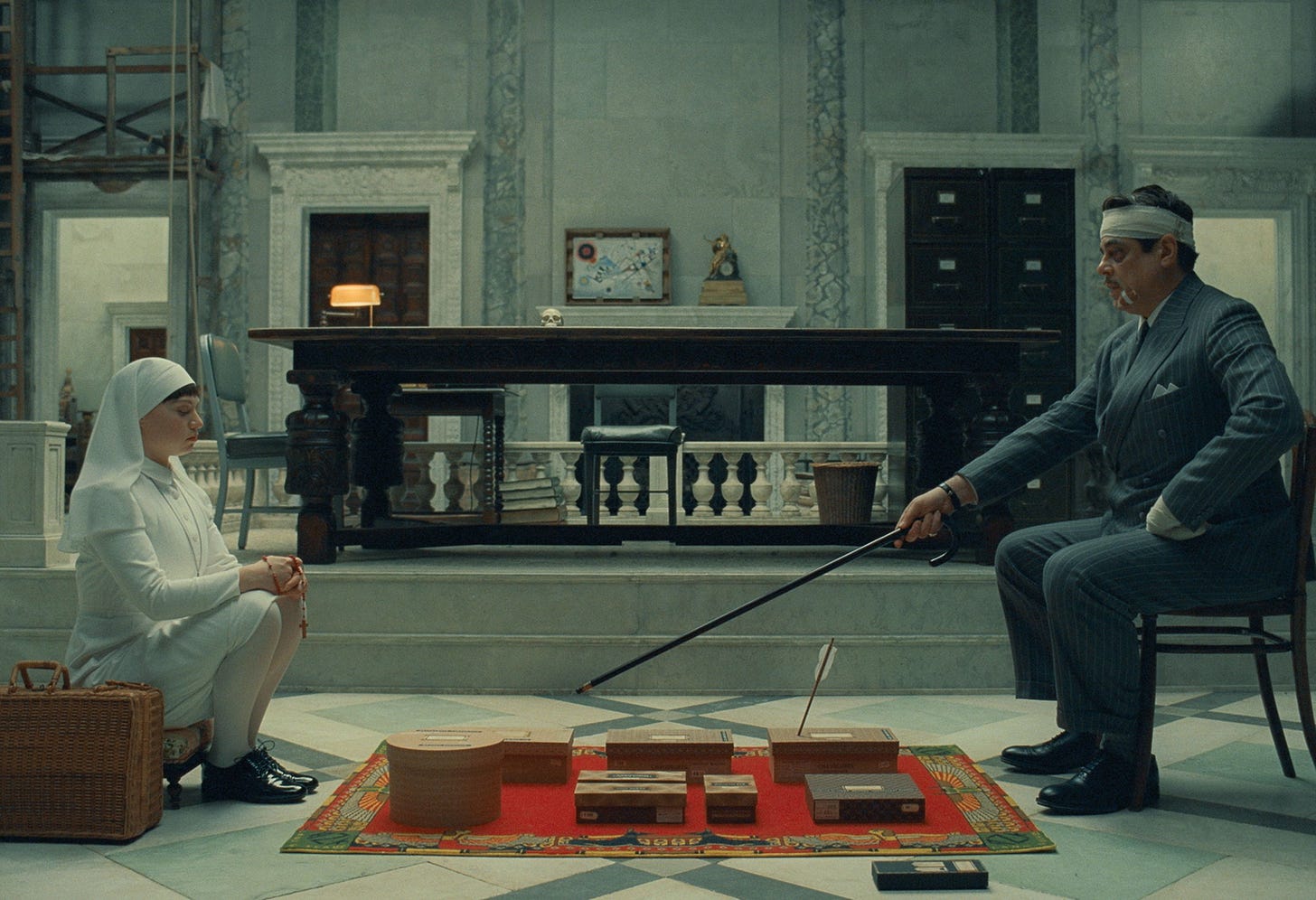

Set in 1950, The Phoenician Scheme follows ruthless arms dealer Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio Del Toro), who survives another assassination attempt. After a brief glimpse of the afterlife, he sets out on a last-ditch mission to redeem himself by reconnecting with his estranged daughter, Sister Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a devout novice nun. As Korda tries to rope Liesl into replacing him at the helm of his corrupt industrial empire, the pair embark on a globe-trotting campaign to salvage his crumbling finances. From sabotaged flights to shady backroom deals, they crisscross the region of Phoenicia conning investors, dodging assassins, and unraveling long-buried family betrayals—including the real story behind Liesl’s mother’s death. With a global infrastructure scheme on the brink, enemies circling, and his own conscience waking up, Korda must decide whether to cling to power or finally change.

Wes Anderson Squared

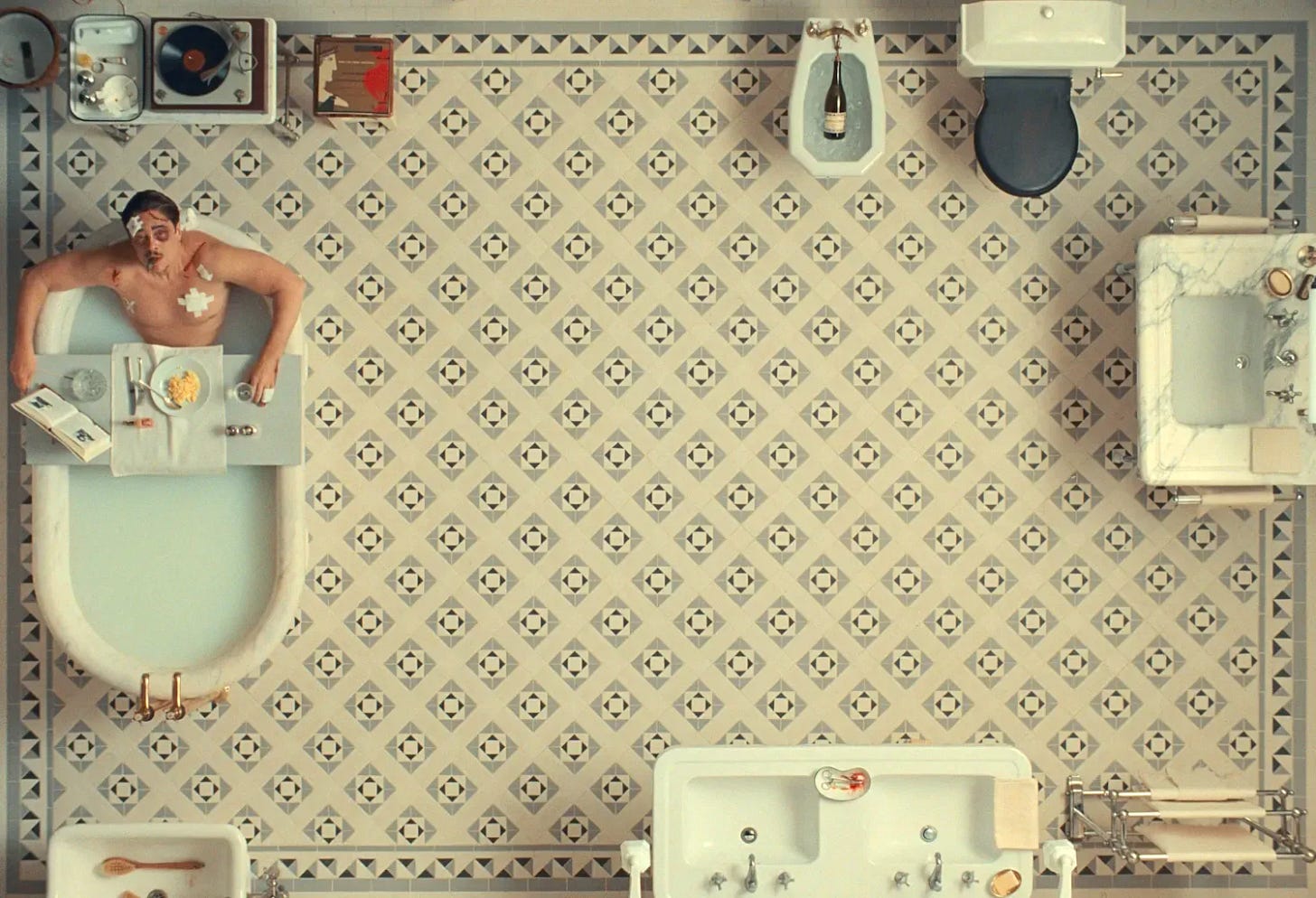

I love Wes Anderson. He’s one of the greatest filmmakers of his generation and has contributed tremendously to the world of cinema. The Phoenician Scheme follows the rigid production standards of a Wes Anderson film to a tee. For better and worse. Let’s start with the former. Top to bottom, this is a gorgeous production. Longtime Anderson cinematographer Robert Yeoman opted out of this project, but the uber-talented Bruno Delbonnel, behind the Coen Brothers’ greatest films, stepped in quite admirably. Visually, the picture doesn’t skip a beat, each frame is drenched with Anderson’s patented pastel color design. Every frame in The Phoenician Scheme belongs on a wall in your house. The visual beauty of the film isn’t surprising, as all of Anderson’s work has a meticulous sense of design, with each prop, wardrobe piece, or item of furniture designated a specific purpose. Adam Stockhausen’s production design is first-rate, perfectly matching the film’s perfectionist, dollhouse-like aesthetic. Especially when you consider the fluidity of the camera movement and the classic dollies through different rooms and sets, it puts into perspective the gravity of the work put into each Anderson production. Desplat returns to deliver another classic Wes Anderson score that’s delightful to the ear. Still, no matter how impressive Wes Anderson productions tend to be, it’s what we’ve grown accustomed to. Working with nearly the same people for over fifteen years, his style has more or less remained rigid to his interests. Hidden in there is both a compliment and a cautionary warning.

The Hitchcock Syndrome

Wes Anderson has gained enough clout to hand-pick nearly the same cast and crew on every project, build the same beautifully designed sets, and overall have a level of cinematic liberty only afforded to a handful of filmmakers. This I call the Hitchcock Syndrome. After a certain point, Hitchcock was able to work with the same people and make nearly the same film time and again. The beautiful blondes, stunning locales, rife tension, wrongly accused men, etc., etc. Then, what makes this a syndrome? Doesn’t every filmmaker crave this artistic consistency? While Hitchcock was largely able to maintain consistent quality, even toward the end of his career, audiences tired of his style with yesteryear releases like Torn Curtain and Topaz. Yet Hitchcock understood that even if his films repeated themselves, each was packaged in a slightly different form and, most importantly, delivered exactly what he set out to achieve: first-class entertainment. Unlike Hitchcock, Wes has never been a man of the masses, amassing a largely niche fan base. But ever since Asteroid City, even an avowed fan like myself has started to question whether Wes has been losing his way. With Asteroid City came one of the most disappointing cinematic experiences in recent years, where I finally sensed what some critics have been saying all along. Every ounce of Wes’s trademark humanism—or even a basic connection to reality—was shredded before my eyes. It’s as if he’s forgotten what he wants to achieve with his pictures. While Hitchcock sought to entertain, Wes’s cinema sought to arouse empathy. Now, seemingly at ease within his well-established creative circle, Anderson prioritizes maintaining his style above all else, forgetting the characters at the core of it. What I see now is a man so steeped in routine that he’s forgotten what’s made his cinema so resonant: soul.

Take your daughter to work

Let’s return to The Phoenician Scheme. To Wes’s credit, the film is a far more concentrated story than recent efforts, centered around the trio of Del Toro, Threapleton, and Cera. Blending espionage, adventure, and family drama in his most commercial film since Isle of Dogs, Anderson struggles to find a consistent tone or emotional rhythm. The espionage thriller and adventure elements are too light and undefined to garner any excitement. The whole narrative is relatively mundane, as the trio moves from one destination to another, pulling off deals that do little to advance the characters or their arcs. It’s almost as if the film is too embarrassed to have any real fun. Instead, we're left with a few smart-alecky quips that barely earn more than a chuckle. Even if the action is unexciting, the plot details are so convoluted and overly detailed that they’re almost intentionally rendered meaningless to make room for the emotional progression of the father and daughter. Yet, the film is never emotionally honest enough to process a serious moment between characters, so any attempt to explore these fractured relationships remains superficial. Wes’s characters speak with such an intense, dry wit that characters seem afraid to emote a single true emotion. And, no film should be straight-jacketed that way.

This emotional detachment bleeds into the film’s larger thematic ambitions. There’s a through line of Christian guilt and the question of redemption for a man steeped in sin, but the film only brushes the surface. Religious imagery and moral reckoning are either played for laughs or pushed to the sidelines. Wes Anderson flirts with surrealism in a series of black-and-white “heaven” sequences, visually reminiscent of Fellini and Buñuel, but they feel more like aesthetic exercises than vehicles for insight. Despite its globe-trotting scope and ornate production design, The Phoenician Scheme feels emotionally vacuous, as if a computer described human connection rather than the real thing. Any attempt at spiritual or character growth is drowned out by the director’s increasingly mannered style, which has come to feel less like a tool for storytelling and more like the story itself. So when Korda eventually turns toward redemption, it registers not as catharsis, but as a narrative inevitability, not earned.

Anyone in there?

There hasn’t been a film of Wes Anderson’s this forgettable. But, I guess there’s a first for everything. Before our eyes, he’s become the very antithesis of what made him so great. A humanist. No longer does he seem to care for people, but rather objects and gimmicks. Some claim Wes is in the “existential” phase of his career, suggesting his films no longer need the emotional depth of his earlier work. I call phooey on that. It’s a cop-out that avoids confronting the decline in quality, in which his work has been slowly regressing into pastiche. If you put a gun to my head and asked me for any moments in The Phoenician Scheme that stand out, pull the trigger. It’s a Wes Anderson film, alright. With all the mannerisms and identifiable features of one. But Anderson’s cinema was never about adhering to a brand. What made people gravitate toward his cinema was that, in addition to the markedly unique style, was how they felt when watching them. The beautifully rendered moments of human love and suffering. There aren’t too many filmmakers where I can list off scenes that are forever ingrained in our brain, like Wes Anderson:

Paltrow and Wilson meet again for the first time in The Royal Tenenbaums

The glances between Saoirse Ronan and Tony Revolori in The Grand Budapest Hotel

It’s disheartening to see a filmmaker once known for stirring deep emotion now making films that feel less like literature and more like glossy coffee-table books. Despite all the complicated sets, pinpoint camera movements, and obvious effort behind the camera, this feels like a film made by someone going through the motions.

I think his style being parodied by AI film makers was a bad foreshadow for him.

"One almost wishes that Anderson had skipped the movie and gone straight for the coffee-table book, which would no doubt be exquisite."

Alonso Duralde in The Film Verdict

OUCH! But also - pretty fair comment actually.